David McFall R.A. (1919 - 1988)

Sculptor

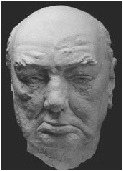

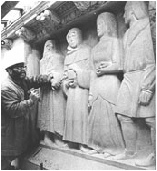

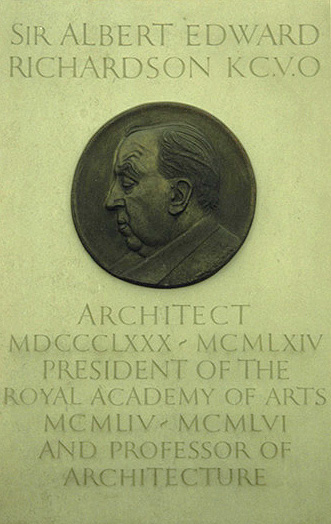

1965/1 Sir Albert E Richardson posthumous relief

In the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral London (unveiled 2/3/1965)

Bronze memorial plaque (Corinthian foundry) on inscribed stone

Lettering (from McFall’s diary)

30/12/1964 Lettering A

31/12/1964 RCHITECT SIR

1/1/1965 ALBERT E

4/1/1965 DWARD

5/1/1964 RICHARDSON

8/1/1965 K.C.V.O.

11/1/1965 MDCCCL

12/1/1965 XXX - MCMLXIV

13/1/1965 PRESI

14/1/1965 DENT OF THE ROYAL

15/1/1965 ACADEMY OF ARTS

19/1/1965 MCMLIV - MCMLVI

20/1/1965 AND PRO

22/1/1965 FESSOR OF ARCH

25/1/1965 ITECTURE

26/1/1965 feathering the serifs

Sir Albert Edward Richardson K.C.V.O., P.P.R.A., F.R.I.B.A, F.S.A.,

(London, 19 May 1880–3 February 1964) was an architect who greatly admired the Georgian style. From 1919 until his death, Richardson lived at Ampthill, Bedfordshire, in an 18th century townhouse in which he initially refused to install electricity, believing that his home needed to reflect Georgian standards of living if he was to truly understand their way of life, though he was later convinced to change his mind by his wife. Their daughter Elizabeth Hill Richardson married the much loved jazz musician and broadcaster Humphrey Littleton.

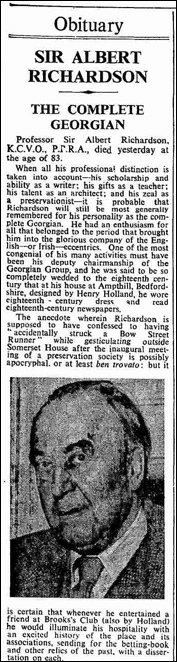

Times obituary February 4 1964

SIR ALBERT RICHARDSON THE COMPLETE GEORGIAN

Professor Sir Albert Richardson, K.C.V.O., P.P.R.A., died yesterday at the age of 83. When all his professional distinction is taken into account - his scholarship and ability as a writer - his gifts as a teacher; his talent as an architect; and his zeal as a preservationist - it is probable that Richardson will still be most generally remembered for his personality as the complete Georgian. He had an enthusiasm for all that belonged to the period that brought him into the glorious company of the English or Irish eccentrics. One of the most congenial of his many activities must have been his deputy chairmanship of the Georgian Group, and he was said to be so completely wedded to the eighteenth century that at his house at Ampthill, Bedfordshire, designed by Henry Holland, he wore eighteenth - century dress and read eighteenth-century newspapers. The anecdote wherein Richardson is supposed to have confessed to having "accidentally struck a Bow Street Runner" while gesticulating outside Somerset House after the inaugural meeting of a preservation society is possibly apocryphal. or at least ben trovato: but it is certain that whenever he entertained a friend at Brooks's Club (also by Holland) he would illuminate his hospitality with an excited history of the place and its associations, sending for the betting-book and other relics of the past, with a dissertation on each. Richardson's anachronism was not an assumed attitude or pose - he seemed genuinely to live and think "in period" - and although he held sound views on the essentials of architecture as being basically a matter of order and proportion, he seemed progressively to blind himself to the possibility of such principles applying equally to the newer trends and methods of construction, or to the less stylistic architecture emerging from them.

TEACHING QUALITIES

The fact is that Richardson was prominently among the last, and most colourful, of a generation of architects in whose lifetime the pendulum had swung from an over-preoccupation with bygone modes to an interest in meeting the aesthetic challenge inherent in the use of new functions and techniques. Looking chiefly towards the past, Richardson, like others of his school of thought, proceeded to justify this instinctive rather than rational preference with arguments which were given wide popular currency by the press and, later, broadcasting. These, perhaps more than conversational indiscretions easily condoned by friends, tended occasionally to strain the affection and indulgence in which Richardson was held by a younger generation of architects convinced of the need for a more realistic approach to architectural problems than the ritual exchanges of verbal broadsides in the "battle of the styles" in which Richardson loved to engage. Nevertheless, the respect in which he was held by his many past pupils showed that his qualities as a teacher far out-weighed the limitations his opinions set on the subjects he taught. Richardson's value as Professor of Architecture, first at University College London. and subsequently, until 1956, at the reconstituted Royal Academy Schools, was universally recognized. As a writer on the architecture of the period which inspired him he also stood in the front rank. At least one of his books, Monumental Classical Architecture in Great Britain and Ireland during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, ranks as a standard work. Other Publications included London Houses and Regional Architecture in the West of England (both with C. Lovett Gill), The Old Inns of England, The Smaller English House (with H. D. Eberlein), and The Art of Architecture (with Hector 0. Corfiato).

EXPLOSIVE UTTERANCES

Much of Richardson's architectural work before the war was done in partnership with Mr. Charles Lovett Gill, with whom he was joint architect to the Duchy of Cornwall Estate in Devon. Among the buildings for which they were responsible were the Public Schools Club, Berkeley Street: New Theatre, Quay Street, Manchester: Southampton Hall, Holborn- Moorgate Hall, Finsbury Pavement: the facade of Regent Street Polytechnic, the Jockey Club, Newmarket: and St. Margaret's House, Wells Street, for which the firm received the 1931 R.l.B.A. Bronze Medal, together with several country houses and the reparation of churches and other ancient buildings. After the war Richardson worked in partnership with Mr. E. A. S. Houfe (his son-in-law). Their commissions included the restoration of war-damaged St. James's Church, Piccadilly: the Church of the Holy Cross, Greenford; the altar for the Battle of Britain Memorial: the Far East War Memorial at Elston Church, Bedfordshire: the Financial Times building near St. Paul's Cathedral: and the rebuilding of Merchant Taylors' Hall in Threadneedle Street. Richardson, who was born in 1880, was knighted in 1956 after he had become president of the Royal Academy. Among his memberships, as well as that of the Georgian Group, were the Standing Commission on Museums, the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), the Royal Fine Art Commission, the Central Council for the Care of Churches, and the diocesan advisory committees of London, St. Albans, Ely, and Southwark. Richardson was a short, stoutish, vivacious man who might pardonably have been mistaken for an actor. The cream of Richardson was best to be appreciated at first hand rather than quoted, when he was on his feet and his own ground, his rapid and explosive utterance giving point to a witty choice of expression whose extravagance was readily "discounted for" by those who knew and loved him. Occasional over-statement and inconsistency in attacking what did not conform to his preferences did not lessen his value as a fighter on the side of the angels, if perhaps more trenchantly and constructively in the field of preservation than in the newer one of an architecture serving contemporary social needs. He married Elizabeth, daughter of John Byers, of Newry, County Down, and had one daughter. His wife died in 1958. He became F.R.I.B.A. in 1913, receiving the Institute's Gold Medal in 1947, was elected A.R.A. in 1936 and R.A. in 1944. He was also F.S.A., Hon. M.A. (Cantab.), Hon. Litt.D. (Dublin) and Hon. R.W.S.

All rights reserved

| Animals |

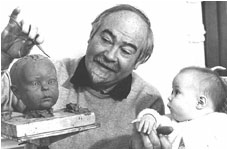

| Busts and Heads |

| Children |

| Churchill studies |

| Lettering |

| Medals coins plates |

| Reliefs |

| Stone carvings |

| Contemporary British Artists |

| On Epstein |

| Picasso |

| The art of portrait sculpture |

| Letters |

| Palliser |

| Son of Man |

| Press |

| Obituaries |

| Memorial address |