David McFall R.A. (1919 - 1988)

Sculptor

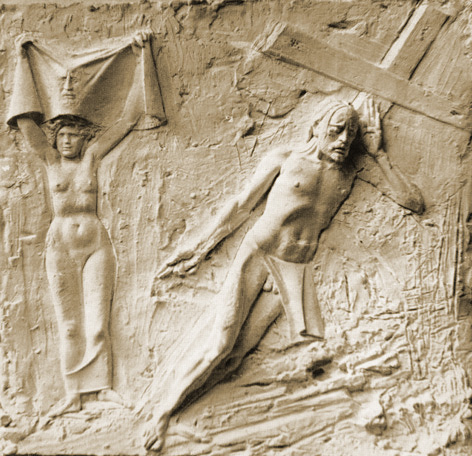

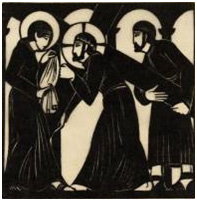

1971/4 The Sixth Station of the Cross

Bas relief

18" x 17" high

Pate ferrugineuse moulee

Exhibited Royal Academy Summer Exhibition 1971 Catalogue No. 1043

Also known as "Jesus and Veronique"

The Sixth Station: Veronica wipes the face of Jesus. Slipping from the crowd, Veronica

removes the veil from her head and without words wipes the face of Jesus. It is an

act of courage and compassion, so graced with tenderness and respect that no one

dares interrupt or interfere. Veronica is holding the cloth with the im print of Jesus'

face.

print of Jesus'

face.

A traditional depiction of the Sixth Station

Sixth Station by Eric Gill

The Stations of the Cross: In almost every Roman Catholic church, 14 carved or painted panels depict the stages of Christ’s final journey, from his judgment in the house of Pilate, to his burial in the Holy Sepulchre. Some, like Eric Gill’s sublime bas-reliefs in Westminster Cathedral (based on his woodcuts), are masterpieces. Many are in more dubious taste, painted plaster for a mass religious market.

Taste, however, is beside the point. For centuries, these “Stations”, or stopping points on the Way of the Cross, have provided ordinary Christians with a virtual pilgrimage and a school of meditation – a method for following Christ’s sacrificial road to death.

Conventional prayers and hymns have been associated with the Stations for centuries, but no set prayers or actions have ever been formally required. All that is necessary is that one moves round the building, meditating for a few moments on the unfolding of the Passion at each stopping place. The Stations need not even be pictures: each can be represented by a simple cross. Intriguingly, Church law stipulated that this cross must be of wood, not stone or paint or metal. That requirement linked the Stations firmly to the doctrine of the Incarnation, a brute physical insistence that the Son of God died on a wooden cross, at a given time and place.

The Stations derive from stopping-points on the route followed by medieval pilgrims round the Holy Places in Jerusalem. But dangerous and costly pilgrimage to a remote city under Islamic rule was possible only for the elite and the intrepid. Local replicas of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre had been common pilgrimage venues for centuries. By the 15th century, clergy who had been to Jerusalem set about recreating the Via Dolorosa for their stay-at-home brethren in the monasteries and churches of Europe.

To begin with, devotional routes were created out of doors. Carved pillars marked the route at distances allegedly the same as those between the corresponding sites in Jerusalem. Martin Ketzel, who created one of the earliest set of Stations, in Nuremberg, lost the measurements he had painstakingly made in Jerusalem in 1468, and went back a few years later to re-measure the route. The inner journey of the soul must not be separated from Christ’s actual progress to the Cross.

No two early sets of Stations, however, included the same scenes. Some had dozens, some as few as seven. This reflected the situation in Jerusalem, where the route of the Via Dolorosa was agreed only at the end of the Middle Ages. So the modern list of 14 Stations evolved outside the Holy Land, in the devotional literature of late medieval Germany and the Netherlands. The list was drawn partly from the Gospels, and partly from pious legend. Eventually, those 14 topics found their way back to Jerusalem, where they helped to determine the sites shown to pilgrims by the Franciscan friars whom the papacy had appointed custodians of the Holy Places.

It was the Franciscans who spread the Stations through the wider Church. In 18th-century Rome, the great Franciscan revivalist St Leonard of Port Maurice, the Billy Graham of his day, fired the imagination of Europe with a series of famous Station devotions preached in the Colosseum. Representations of the Stations, till then largely restricted to Franciscan churches, rapidly became essential items in every Catholic church. By the mid-19th century they had become as distinctive of popular Catholic piety as the Rosary.

The Stations embrace tragedy, while insisting that life has purpose. They represent the paradigmatic human life of the God-man as a journey through suffering and loss to the sorrow of the tomb. But the stops along the way – his Cross carried by Simeon, his face wiped by Veronica – are filled with tenderness. At the end of that terrible journey is the hope of Resurrection.

The Stations have exercised a universal appeal because they provide a metaphor for the bitterness of lived experience, while insisting that beyond sorrow, we are on a journey into meaning and hope. In a culture mired in a despairing hedonism, that message retains its power to transform lives.

Eamon Duffy, Professor of the History of Christianity at the University of Cambridge

All rights reserved

| Animals |

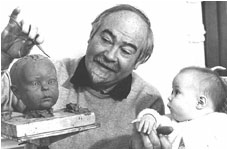

| Busts and Heads |

| Children |

| Churchill studies |

| Lettering |

| Medals coins plates |

| Reliefs |

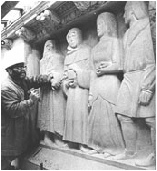

| Stone carvings |

| Contemporary British Artists |

| On Epstein |

| Picasso |

| The art of portrait sculpture |

| Letters |

| Palliser |

| Son of Man |

| Press |

| Obituaries |

| Memorial address |