David McFall R.A. (1919 - 1988)

Sculptor

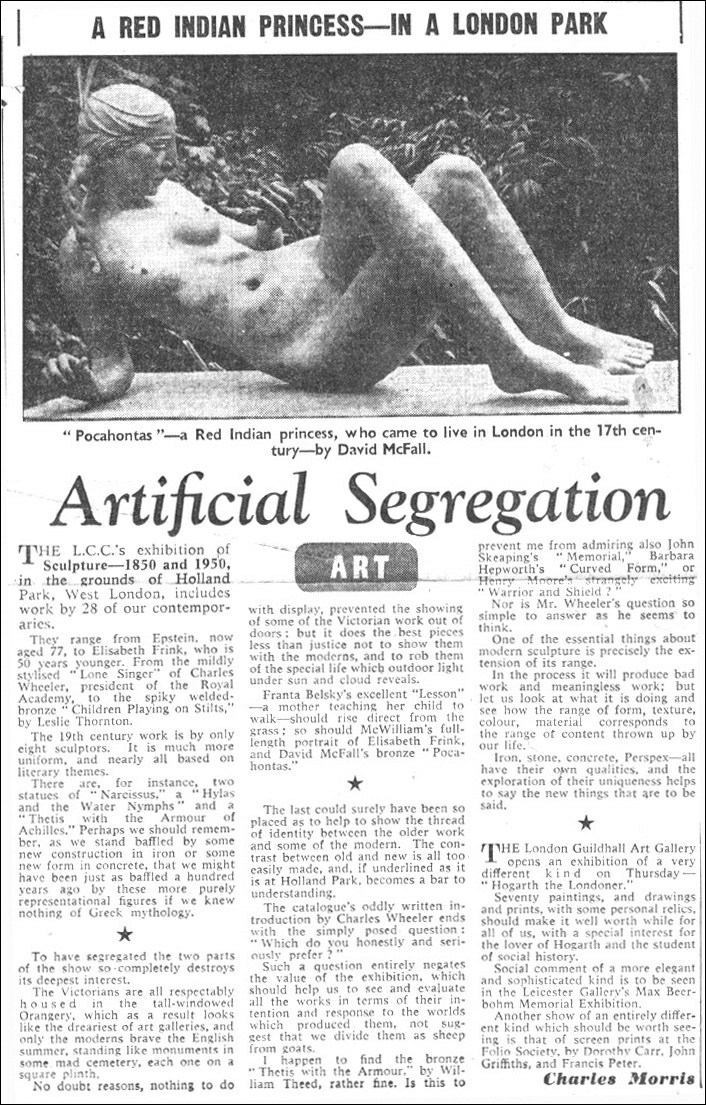

1955/4 Pocahontas "La Belle Sauvage"

Length 61¾" x width 27¾" x height to top of feather 35”; height to top of head 31” excluding bronze base (1¼") - Signed McFall 1955 on corner behind elbow. Mounted on green wood plinth 22" high with brass plate "Pocohontas La Belle Sauvage by David McFall"

Bronze (cast by Gaskin foundry)

Commissioned by Cassell’s Publishers for new premises at 35 Red Lion Square, London; later moved to Greycoat Place Victoria and later to Villiers House, The Strand WC2.

Exhibited Royal Academy Summer Exhibition 1956 Catalogue No. 1347

Exhibited LCC Holland Park exhibition ‘Sculpture 1850 and 1950’

A cast (probably the original) was sold by Christies 21 March 1996 London, King Street (Modern British Art)

References:

1) Daily Telegraph 24/4/56 Sir Winston Churchill laying the foundation stone at Cassell's.

2) Birmingham Post 24/4/56 report of the Cassell's foundation stone laying by Churchill: "... To retain the firm's link with La Belle Sauvage, and that neighbourhood's own fanciful connection with the Princess Pocohontas, Cassell's commissioned a larger than life size statue of the "Beautiful Savage" to grace the entrance of the firm's headquarters. The statue, which weighs a ton, is the work of David McFall A.R.A. It is to be shown at the summer exhibition of the RA."

3) Peter Greenham CBE, RA, PPRBA, Keeper of the Royal Academy private letter 17/2/83: "The statue of Pocohontas, in Holborn, is to my mind the best to be erected in London since Epstein's Madonna in Cavendish Square".

4) "London Statues" by Arthur Byron (published Constable London 1981) page 182 with photograph: "...Pocohontas appears as an attractive nude with 2 pigtails and the two feathers sticking out of her hair are crosswise".

5) Letter from Desmond Flower former Literary Director of Cassell and Company Limited 4/10/88 "...It was I who commissioned the Pocohontas which used to stand in Red Lion Sq - I still have the maquette - and introduced him to Winston Churchill, his bust of whom stood over the foundation stone which WSC laid"

6) Public Sculpture of the City of London by Philip Ward-Jackson – 2003: “McFall's special penchant for the female nude was exemplified over the years in such works as the Pocahontas “

6) West London Press 6/4/56: “The reason that Cassells have chosen Pocohontas is because she stayed at an inn at Ludgate Hill, which Cassells took over and converted into offices in 1853. The inn was called La Belle Sauvage (the beautiful savage) after Pocohontas.”

"La Belle Sauvage" – Bell Inn in London, owned by a proprietor named Savage, had been a residence of Pocahontas during her visit of 1616-17. A century later, Joseph Addison in one of his Spectator essays renamed it "La Belle Sauvage" ("The Beautiful Savage") in honour of her. He could think of a heroine born and nurtured in a natural environment only as a person of beauty. See Pocahontas, La Belle Sauvage (London, after 1956); this flyer discusses the bronze sculpture of Pocahontas by David McFall commissioned by Cassell Publishing House in 1956.

Pocohontas story: Princess Matoka Pocahontas, daughter of Powhatan hereditary Overking of the Algonquin Indians of Virginia born 1595 died 1617. The Virginian settlers who first settled on the banks of the Potomac River in 1607 encroached on an Indian preserve, so not unnaturally conflicts arose and a Captain John Smith was made prisoner and would have been clubbed to death had it not been for the intercession of the Chief's daughter, Pocohontas. She was later inveigled into the English colony, made a Christian and married John Rolfe, and even sailed to England with a dozen Indians in her retinue. Thus she met James I's wife, Queen Anne, a number of times. At the start of her return to America she fell ill and died and was buried at Gravesend in 1617, aged probably 22. At Gravesend there is an overlife size statue of her presented by the people of Virginia.

An Introduction to "Pocahontas: Her Life & Legend" by William M.S. Rasmussen and

Robert S. Tilton

She has been called America's Joan of Arc because of her saintlike virtue and her courage to risk death for a noble cause. She has even been revered as the "mother" of the nation, the female counterpart to George Washington. Her rescue of Captain John Smith is one of the most famous and appealing episodes in all of our history. Few figures from the American past are better known than the young Powhatan woman who has come down to us as "Pocahontas."

She was born into a culture that had some knowledge of Europeans, and after their settling on the outskirts of the territory controlled by her father, she was apparently drawn to these peculiar strangers. A number of the chroniclers of the Jamestown founding mention her by name and note her interactions with the English settlers. This Powhatan girl, who was reported to have saved John Smith from execution and to have enjoyed cartwheeling naked with the young boys of the Jamestown settlement, would as a young woman be kidnapped as a political pawn, converted to Christianity, married to a settler, and taken to England as an example of the potential of the New World for cultural indoctrination. It was among members of her adopted nation that she took sick and died, at age 22, as she attempted to return to her homeland.

The fame of Pocahontas began in her own lifetime. Contemporary Londoners welcomed with excitement a figure who was living proof that American natives could be Christianized and civilized. By the beginning of the 18th century, the reputation of Pocahontas was well established. Readers in England and on the Continent had come across her exploits in the popular travel literature of the period, and vignettes of her life had been included on maps of the New World.3 Robert Beverley reverently told of her in his history of Virginia; Joseph Addison honoured her in an essay in the Spectator; and a Boston schoolgirl painted her portrait. As Europeans of the 18th century looked back to the natural nobility of "primitive" cultures, the legend of the virtuous Pocahontas served as a useful model.

The 19th century saw the greatest dissemination of the Pocahontas legend. This was the period in which the brief history of America came to be recognized as containing the types of elements that could be used in the construction of romantic visual and literary narratives. During the first decade of the century her story had been wrested from the exclusive purview of historians by novelists and dramatists, who had noted the potential in the great events of her life for stirring fictional portrayals. Portraitists rendered her image, and history painters recreated and glamorized her accomplishments. Politicians debating the "Indian problem," abolitionists, and sectionalists all manipulated her story for their own devices, and her likeness was to be seen on numerous advertisements for tobacco and medicine. Vessels of various sorts were named after both Pocahontas and Powhatan, as trains would be in the 20th century. Towns, cities, and counties also adopted the names of the great Indian figures of Jamestown. The world record as the fastest horse in harness was held by the great pacing mare Pocahontas from 1855 to 1867. And while historians hotly debated the credibility of Smith's record of her life, one company of Confederate soldiers carried her image on a ceremonial banner.

Over the centuries since its creation, the Pocahontas narrative has so often been

retold and embellished and so frequently adapted to contemporary issues that the

actual, flesh-and-blood woman has long been hidden by the ever-burgeoning mythology.

This young woman, who was known among her own people as "Matoaka" and whose nickname

was "Pocahontas" ("little wanton" or "little plaything"), was an eyewitness to the

convergence of two disparate cultures. Although she apparently possessed a number

of extraordinary qualities, including a spirited and engaging personality, it must

be remembered that what we know about her life has been lifted from the narratives

of English males, all of whom brought their particular fantasies and prejudices to

bear on their representations of the New World and its people. The daughter of Powhatan,

whom Europeans dubbed a "king" and an "emperor," which made his daughter a "princess,"

left no words of her own.

SMITH RESCUED BY POCAHONTAS 1870, Christian Inger (after Edward Corbould) - While some 19th-century images of Pocahontas highlighted her marriage to John Rolfe, countless others focused instead on her feelings toward John Smith. Most historians doubt that a full-fledged romance ever existed between Pocahontas and Smith, but this notion was widely spread in the early 19th century, sparked by writer John Davis, who transformed Pocahontas into the heroine of an elaborate romantic narrative. This 1870 lithograph shows a Pocahontas typical of such representations—Europeanized and overly nubile for an adolescent girl. It also bears inaccuracies common in late 19th-century artwork, when headdresses, horses, and tepees (the latter not seen in this detail), which are trappings of Western Plains cultures, became generic icons for all "Indians."

All rights reserved

| Animals |

| Busts and Heads |

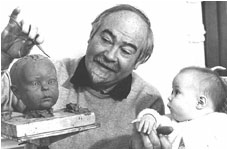

| Children |

| Churchill studies |

| Lettering |

| Medals coins plates |

| Reliefs |

| Stone carvings |

| Contemporary British Artists |

| On Epstein |

| Picasso |

| The art of portrait sculpture |

| Letters |

| Palliser |

| Son of Man |

| Press |

| Obituaries |

| Memorial address |